|

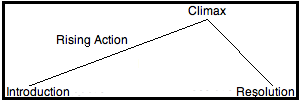

Plotting The Perfect StoryWhy You Should Always Plot First Plotting a story well is key to building a cohesive narrative. There's no right way to do it. Writing is highly personal so every writer approaches each story differently. Good creative writing needs several elements to be working in harmony. It requires good structure, good characterization, and, of course, a good plot. This is oversimplification but there is no doubt that these all need to be in play for a story to work. Building the key points of the story before writing it helps the structure but can leave the characterization weak. Plot and characterization depend on each other. Well-developed characters can’t run around a world with no action or conflicts nor can they look like puppets, reacting exactly as if everything they say and do is being strictly controlled by the author. The Basic Structure Before writers can do too much experimenting or tinkering with structure, they should understand the basic principals of plotting a story. Imagine the story as a triangle. It starts with the Introduction. We meet the characters, discover the setting and learn about the initial conflict. Next is the rising action. The characters try to overcome the central conflict until it reaches a climax. The climax is the main event where all or most of the central conflicts are resolved. Finally the story reaches its resolution. The action winds down, consequences and rewards are doled out, and we reach the end.

Finding the Right Structure Many modern stories stray from the classic plotting model, or modify it to fit the story’s needs. However, it’s important to understand why this structure is the norm. The structure is based on action. It’s the force that drives most stories. Action doesn’t necessarily mean James Bond jumping off a 100 meter cliff as he’s trying to put on a parachute that he can only hope will open, although Ian Fleming proved that that’ll keep us reading, but the reader needs action, or the promise of action. It can be opening a letter or defusing a bomb. This story structure is built on the basic principals of suspense. The reader should always have to ask, “what happens next?” Once you understand the principals of suspense, feel free to divert from the classic triangle. As in poetry, it’s the content of the story that informs the structure. If the story takes place over a 70-year span, obviously there are chunks of time that are going to be omitted. Some of the story may be told in flash backs or it may use parallel story lines. Sara Gruen does this well in her best selling novel Water for Elephants. The story starts by introducing a 90 year-old man with a bad temper living in a nursing home. However, the majority of the novel’s action takes place 70 years before, when the protagonist was the veterinarian for a traveling circus. The connections between the desires of the 20 year-old and the desires 90 year-old is one of the compelling aspects of the book and it’s achieved through structure. Gruen uses parallel storylines, flashbacks, to contrast the two. However, maybe your story takes place over the course of just one or two days, maybe as little as an afternoon. For stories that take place in this short of a time span, usually chronological order is the most logical choice, but not always, it depends on the needs of the story. Try different approaches. What will it do for the story if you start it right before the climax, then build the story up in flashbacks? What will it do if you start at the beginning and flash forward? Think about every angle of approach, make a list highlighting the ways that seem logical to you and eliminate those that don’t. Juice It Up Add as much conflict as you can. Conflict is the juice of any story (unless you’re Gertrude Stein), it’s what we write to resolve. Add conflict until the characters are drowning in them, then add more. Don’t lock yourself into solving all of the conflicts at the climax. Think of the story not as one large triangle, but as several little triangles making up the whole. Some conflicts may be resolved before others and some are introduced by the solution of another. Point Of View One last hint for plotting the story and finding the right structure. Know and utilize the right point of view (POV). POV is one of the trickier parts of structure to get right and too many writers don’t give it enough thought. How close do you want your reader to be to the characters? The three basic POVs are first person (I wrote the story), second person (You wrote the story), and third person (He wrote the story). Very few stories are written in second person because it’s the most difficult to write and it can be jarring for the reader. The author is telling the readers what they’re thinking, feeling, and doing, and often the reader is following along thinking, “I’d never think/feel/do that.” Readers like to watch more than participate. But it can be done, especially when the story is meant to cause discomfort and self-reflection. Junot Diaz wrote a successful story using second person called, “How To Date a Brown Girl (Black Girl, White Girl, or Halfie).” It ran in the New Yorker's December 25th Issue, 1995. Many action based plots, such as thrillers are written in third person because they jump so often from scene to scene, person to person and the author doesn’t want you to know what each character is thinking. Some types of fiction are written in first person, such as the detective novel, because the author wants the readers to follow the main character on his path of discovery. If the story doesn’t fit well into a classic genre, then the POV depends on the needs of the story (even when writing in a genre, know what the POV is doing for the story). Think about how the suspense is going to be developed in the plot and that may give you clues as to which POV to use. Remember, readers like rules. You get to make them, but once established don’t break them (there are exceptions to this rule about rules, just as there are exceptions to everything in writing but tread be careful and know what you’re doing). If you’re writing in first person and suddenly want the reader to know what’s going on somewhere else in the world, you can’t jump into someone else’s head. Conversely, if you’re writing in third person and for the first 50 pages have been only revealing the thoughts of one character, then your POV is attached to that character and can’t jump into someone else’s thoughts on page 65. Related Articles: Reaching Your Writing Goals... Read More About Fiction Writing Return Home

|

||||

|

|

||||